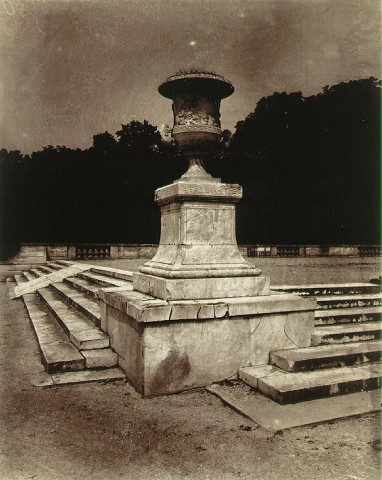

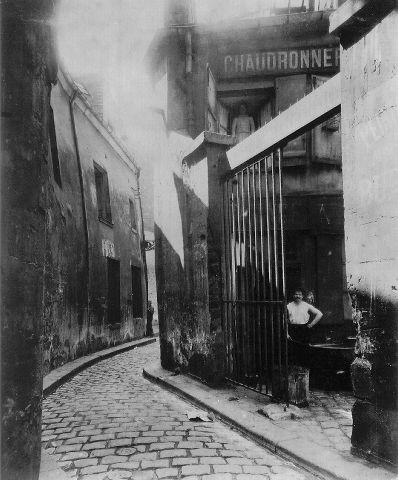

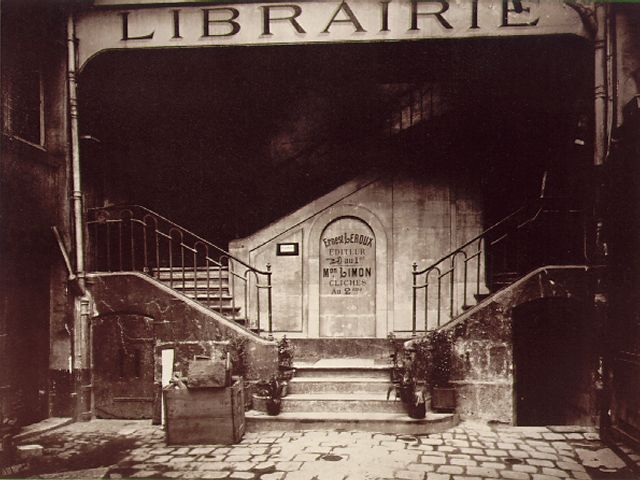

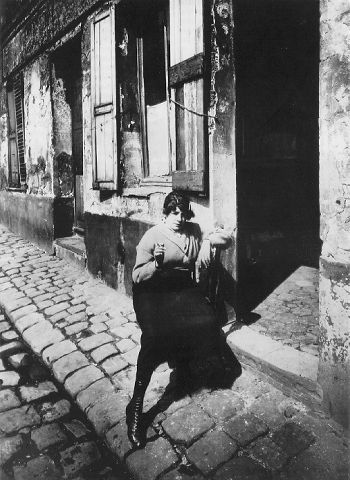

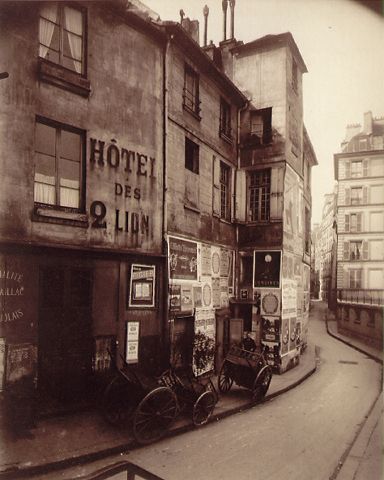

Eugène Atget was a celebrated French photographer, best known for his detailed photographs of Paris and its environs at the turn of the 20th century. Born in 1857, Atget began photographing the city in 1898, using a large format view camera to capture architectural details and street scenes before they disappeared due to modernization. He created an extensive collection of images over his career, documenting Parisian life during a transitional period.

Atget’s work had an enormous impact on generations of photographers with his straight forward yet poignant style serving as inspiration for many greats after him such as Man Ray and Berenice Abbott. With a focus on architecture and associated arts, he produced photos that were idiosyncratic portrayals of Paris before urbanization took over. After Atget’s death in 1927, Abbott discovered much of his work and published it in an effort to introduce him to the wider art world.

Atget is remembered today not only for his impact on photography but also for his unique approach to capturing images of historical significance. With every photo he took, he documented the past so that future generations could understand it better through visual representation. Often overlooked by contemporaries because he produced them pure documentary without any attention paid compositionally or emotionally,Ajtet remains one of France’s most influential photographers despite this reputation for being philosophically sparse with genius artistic intent sometimes seen beneath its profound lackadaisicalness when compared against much more emotionally charged works from contemporaries producing socially stunting imagery during this period .