Ralph Eugene Meatyard was an American photographer and optician who gained recognition for his surreal and thought-provoking photographs. He was born in Normal, Illinois in 1925 and raised in Bloomington before serving in the United States Navy during World War II, though he never saw overseas combat. Meatyard worked as an optician in Lexington, Kentucky while also creating a vast collection of photographs that would later be praised for their haunting qualities.

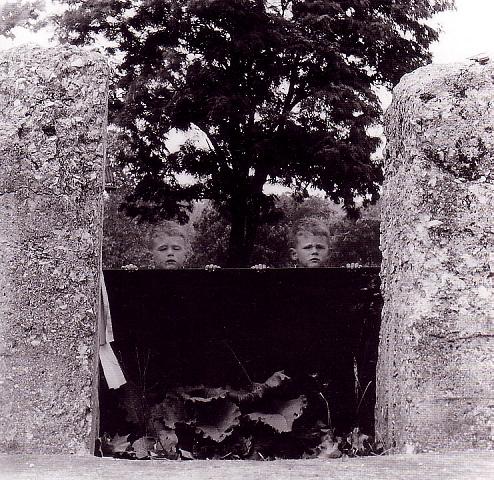

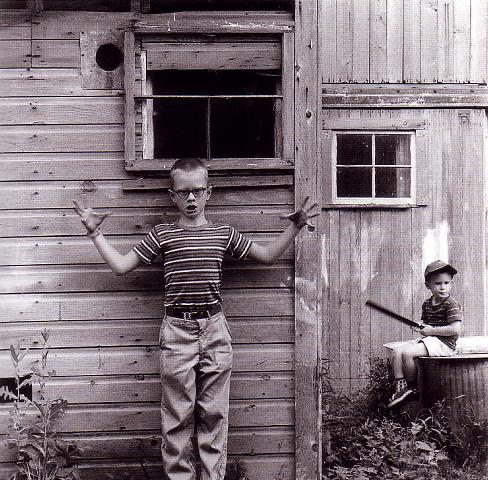

Meatyard’s work often included family members and friends wearing grotesque masks, creating eerie and dreamlike scenes that captured the essence of surrealist photography. His close circle of creative companions included mystics, poets, and fellow photographers who shared his enthusiasm for evocative imagery. Though he received little recognition during his lifetime due to the unconventional nature of his artistry, Meatyard is now considered a critical figure in American photography.

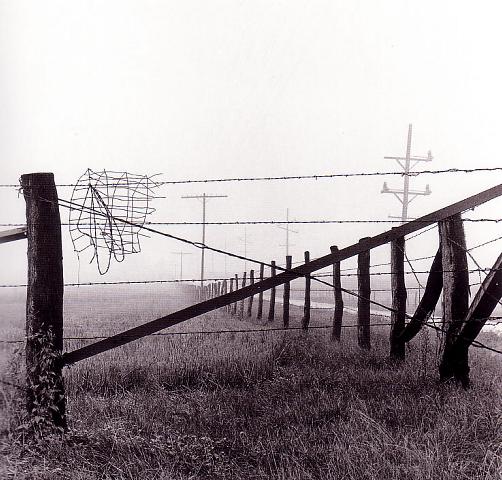

Influenced by literary greats such as James Joyce and Samuel Beckett, Meatyard’s photographs were imbued with deep meaning that left viewers questioning what they were experiencing. The monochromatic tones used throughout many of his images brought out a sense of starkness while the puzzling content kept audiences coming back to examine each detail repeatedly. Despite struggling with health issues towards the end of his life which made it harder to produce new works continuously, Ralph Eugene Meatyard’s legacy has remained secure thanks to how he transformed everyday subjects into an innovative form of surreal photography that continues to inspire fans today.