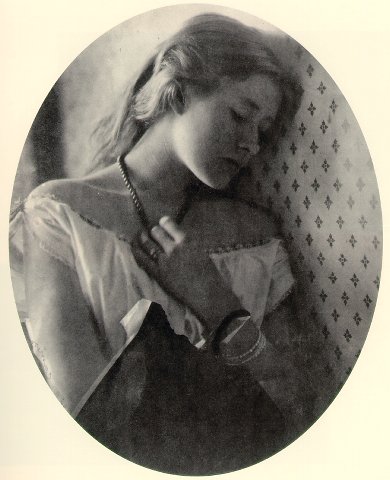

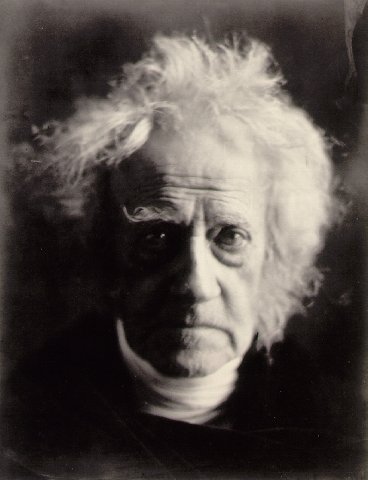

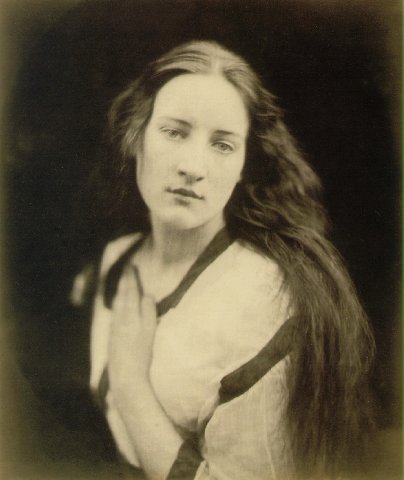

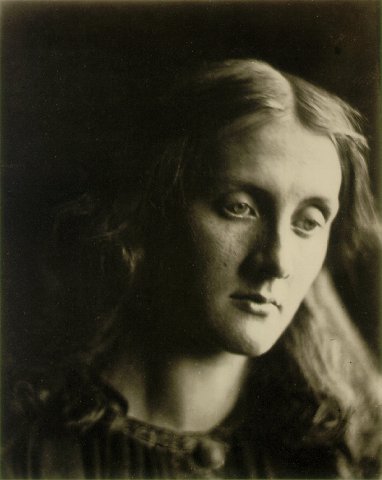

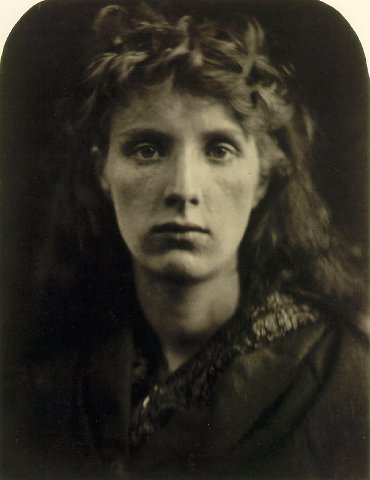

Julia Margaret Cameron, born in Calcutta, India in 1815, was a British photographer known for her outstanding portraits of the distinguished figures of Victorian England and staged allegorical images. Despite having no formal training and being given a camera as a gift at 48 years old, Cameron found photography as her ideal outlet for artistic expression.

Her interest in photography began after receiving the camera and she quickly established herself as one of the greatest portrait photographers of the 19th century. Her photographic career lasted from 1864-1875 during which she produced painterly photographic portraits that captured the soulful gaze of her subjects with delicate handling of light, shadow and composition. Cameron was an original and creative photographer whose works were often misunderstood by critics due to its unconventional style.

Cameron’s legacy continues to stand out as an inspiration to generations after her death in Kalutara, Ceylon in 1879 through continued exhibitions across various art museums globally. She is celebrated for having brought aesthetic values to photography at a time when it was perceived primarily as a science rather than an art form. Her contribution towards shaping portrait photography lies not only on capturing beauty but also on evoking emotions – something which remains relevant even today.